- Read an excerpt

- Buy Unbecoming a Lady on Amazon

A friend knocks on Cora Countryman’s front door seeking help with the torn sleeve of her work dress, claiming she ripped it on a bush. As the town’s seamstress, Cora has mended many a dress. So, when she sees a ragged tear in her friend’s forearm and a bruise left by a thumb, Cora questions her friend’s story. When Cora asks about the wounds, her friend is evasive. Worried by the lack of answers, Cora starts her own investigation.

When murder is done, Cora won’t give in, back down, or submit to the behavior expected of a young lady in 1876 in a burgeoning Illinois prairie town. Why should she, she never expected to stay. That is until her mother abandoned her, leaving her heavily in debt, her reputation on the line, and the drudgery of a boarding house to run for one boarder.

Her intended life of mystery and adventure never seemed so far away.

“Thanks to the superb writing and storytelling skills of D. Z. Church, one of the most authentic and unique protagonists, Cora Countryman, comes alive for you page after page. A grand, grand read.”

—Heather Haven, author of the Alvarez Family Mysteries and the Persephone Cole Historical Mysteries

An excerpt from Unbecoming a Lady:

(1) Sunday, it begins

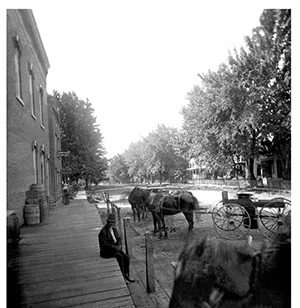

Cora Countryman’s mother had been gone twenty-four hours before it crossed Cora’s mind to worry. Edith Countryman’s carpetbag, two dresses, and a few select items were the only things missing from their house at the corner of Main and Park Streets in Wanee, Illinois, a small town on the edge of the prairie where everyone knew everyone and noticed any goings-on. An influx of workers and their families to feed the burgeoning new businesses continued to turn the sleepy village into anything but, making it even more remarkable that Edith Countryman left without having been seen—if she had.

When her mother had not returned by Saturday night, Cora rented a horse and buggy from Wanee Livery Sunday morning before the liveryman went to church. She drove north two hours past rolling green fields dancing with yellow and lavender wildflowers to her brother’s farm in the next town to the north, Awan, hoping her mother was there. She was not. Jess Countryman hadn’t seen Edith Countryman, nor had she written to him in weeks. Jess rarely came to Wanee, preferring to attend the Evangelical Church in their tiny farming community with his new and pregnant wife on his one day off.

After a late luncheon, Cora headed for home. The rented horse plodded down the roadway under the dappled shade of native walnut, chestnut, and elm trees as Cora sifted through her memories of the weeks before her mother’s disappearance, searching for clues as to where Edith Countryman might be. Foul play seemed out. On the day of her disappearance, Edith had been alive, sharp-tongued, and baking when Cora left for Layman’s Dry Goods store to check if anyone had dropped off a dressmaking or mending commission for her. They had not.

When Cora returned, her mother was out. Cora presumed she was at work in the newly opened library located in Library Hall with the other village offices. When her mother didn’t appear by late afternoon to make dinner for their boarder, Cora did, assuming her mother was chatting with someone she met in the park that occupied the four blocks, about an eighth of a mile, between Library Hall and the Countryman house.

Cora knew little about her mother other than that Edith Countryman had attended a finishing school for girls in Chicago, matriculating with a high school diploma and the ability to quote poetry, embroider, play piano, and Whist. Skills, Edith often noted, that were of little value in Wanee, where few had more than an eighth-grade education, and all newcomers were illiterate heathens. She scoffed when the town broke ground for the library, proclaiming it would remain an empty shell until it offered dime novels for checkout.

Cora admonished herself to be circumspect. It would not do to get everyone all riled up, only to have her mother walk in the door. It was possible, for instance, that her mother had taken the Friday train to Chicago, intending to return Monday, though it was unlikely since she would have told Cora of a weekend trip.