- Read an excerpt

- Buy A Confluence of Enemies on Amazon

“It is really wonderfully written. Congratulations! Intense, grounded in the time and place, and ends with surprises and fireworks galore.”

—Heather Haven, author of the Alvarez Family Mysteries and the Persephone Cole Historical Mysteries

“Cora (is) a character it’s pleasurable to cheer for, resolutely defending … while trying to solve the murder, regardless of the danger to herself. Captivating post-Civil War mystery in a small Midwest town.”

—Booklife

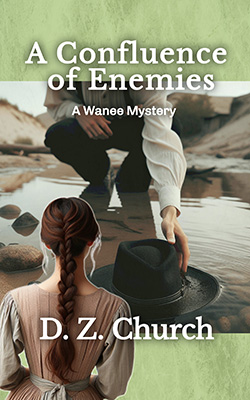

When a body taints the dwindling water supply, can a spirited young woman save her prairie town?

August 1876. Cora Countryman dreams of a life of mystery and adventure, anywhere but confining Wanee, Illinois. Even when the long drought attracts a rainmaker panhandling his own version of fantasy.

As thirst and disease rampage across the railroad tracks, she fights for what little she has. Campers steal her vegetables and raid her water. But when the editor of the newspaper is dumped at the undertakers near death, she fears for her village, already a tinderbox of resentment.

She snatches then hides the newspaperman at her boarding house, endangering all those within her walls. To save him, she determines to solve the killing—no matter the danger to her. Not from disease, drought, or dreadful secrets—but from the men who would stop her.

A Confluence of Enemies is the riveting second book in the historical Wanee Mystery series. If you like a heroine who isn’t afraid of action, is easy to cheer for and has grit, then you’ll love D. Z. Church’s captivating sequel.

An excerpt from A Confluence of Enemies:

Kanady slurped from a canteen worn across his chest bandolero style, a trick he learned during the War. As a breeze blew through the tangle of narrow-leafed willow trees draping the stream ahead, the lowering sun lit a body, legs on the bank, head in the water.

Kanady splashed up the stream. A man lay with his right arm extended into the water, his head resting on it as though he napped. Water flowed around his arm, eddied in the cusp of his neck, and lapped his face. His left arm rode his hip down his dry left side.

From the stench of ammonia and sulfur, the man was dead. With a huff, Kanady slapped a mosquito on his neck as he shrugged out of his knapsack. Bugs swarmed in a swirling cloud rising from upstream pond stagnant behind an earthen dam.

He checked the western sky for the time. The constable would ask. The evening star sat low on the horizon; its bright burn dulled by the wind-driven dust of the coming dusk.

Pulling a handkerchief from his right trouser pocket, Kanady tied it over his nose and mouth before kneeling to study the body. Not only the smell, but the buzzing insects and larvae testified that the body had lain in the watershed for more than a day.

He opened the left side of the man’s suit coat with the thumb and index finger of his left hand. According to the label, the man had bought his black coat and matching trousers from the Marshall Fields store in Chicago. Kanady rubbed the fabric between his fingers. The gabardine felt as new as the bullet hole over the dead man’s heart.

Avoiding the blood stain, Kanady searched the pockets of the man’s coat for identification. The two vertical pinholes found in the left breast of the dead man’s suit coat weren’t a surprise given the man’s dress. Kanady had run into the man’s sort while in his travels to the west. Rail inspectors, union organizers, all sorts of men wore badges these days. And lawmen.

Kanady calculated the odds that the dead man, if a lawman, had tracked him to Wanee. Long was his summation of the odds, but not out of the realm of possibility. A more complete search of his pockets turned up a wooden chip marked as Confederate scrip tucked in the fob pocket of the man’s vest. Kanady toyed with the scrip, waiting for a shadow he’d seen upstream to move.

When it didn’t, he continued his inventory. The man’s boots were in the style some called cowboy, with a slanted heel and rounded toe. When alive, the man had been of average height, average weight, and had his brown hair trimmed by a barber. A muddy hole at the dead man’s feet and the lay of the body telegraphed that he had spun and fallen where he stood.

Guided by the body’s odor, like bayou shrimp gone off, Kanady weighed whether to move the dead man to the bank of the creek or leave him undisturbed. The fact that he had lain in the water long enough to taint it with the disease he carried was a public health consideration. His manner of death was a matter for the constable.

Sitting back on his haunches, Kanady memorized the placement of the man’s arms, legs, and head, knowing the constable would ask. His eyes locked on the man’s wet right wrist. What he saw there stirred memories of rifle fire stripping leaves from trees, leaving a thicket of naked trunks in its wake. Kanady fiddled with the cuff on his left wrist until the thunderous concussion faded from his mind.