- Read an excerpt

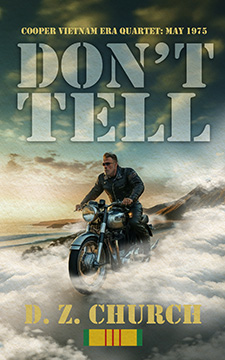

- Buy Don’t Tell on Amazon in Kindle and paperback formats

LT Robin Haas has a problem. Her Leading Chief has disappeared days before his Review Board. It’s not like him to run. His neighbors aren’t much help, but CWO Dan Cisco, back from Saigon, is at her side, burdened by a secret of his own. One that will change both their lives. Laury Cooper, is cleaning up the mess he created in Saigon, when CDR Byron Cooper calls from an aircraft carrier on station in the South China Sea. That’s when everything turns nasty.

Don’t Tell is the fourth novel in the Cooper Quartet, the story of a military family set against the turbulence of the Vietnam Era. It is May 1975. Saigon has fallen to the North Vietnamese, the dead have come back to life amidst shame, anger, and greed. It will take all the Coopers to make this one come out right.

“Church spins a lively tale where motives are unclear in a vividly realized hothouse naval environment. The engaging characters and their detailed histories make this a satisfying capstone to a wide-ranging epic… Fans of family dramas will cheer on the appealing Naval protagonists as they navigate a troubled period of American history.”

—Booklife

An excerpt from Don’t Tell:

May 4, Sunday

Gunner was snoring like a cat freight train; his wet nose jammed in Lieutenant Robin Haas’s ear. He clung to her as though someone would tear her away, leaving him to fend for himself, though he had been spoiled rotten since he was a kitten. Robin reached up to stroke Gunner’s heaving side, knocking the newest issue of Life magazine from her nightstand in the process.

The magazine documented the Fall of Saigon. From April 29 to 30, fifteen North Vietnamese Army divisions had surged through the city to the Presidential Palace. War photographers captured the two-day evacuation as 662 Marine, Navy, and USAF flights airlifted 6,236 passengers to the Seventh Fleet waiting in the South China Sea.

Robin grabbed the magazine from the floor, stuffed her pillows behind her back, and leaned against the bed’s headboard. Gunner climbed onto her lap then to her shoulders as though he knew Navy pilot Lieutenant Harry Stillwater was on the cover. Six and a half years dead, Harry was now back among the living.

Two years ago, Harry’s family had carved an end date on his tombstone and buried relics of him in an otherwise empty grave. One was a scorched copy of Song of the Lark recovered from a crash site outside a ville in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. His dad, Art, had cried, Harry’s sisters, Celeste and Martha, had cried. Mary, his mother, had sobbed as she hugged Robin. The next day, Art drove Robin to the Fargo, ND airport and waited while she boarded her flight, waving as the plane took off. Robin sobbed from Fargo to Chicago to San Francisco to Monterey, California, as with each flight, the wheat fields of Harry’s home became her past.

She opened the Life magazine to a page ruffled from handling. A photo of Cessna 0-1 Bird Dog on the deck of an aircraft carrier in the South China Sea dominated the page. The two-man aircraft was surrounded by men, including Robin’s cousin, Commander Byron Cooper. Some of the men held the struts to keep the airplane from lofting into the air. Some stood by the open right-hand door staring at a dark-haired man on a gurney. A bloody handprint stained the right back window emphasizing the smear on the fuselage beneath the open door.

Robin fingered the black curls of Byron’s brother, Laury Cooper, left untrimmed for his wedding on April 19. Since then, a war had ended, the dead had come to life, and everything Robin thought she knew had transmogrified into the unimaginable.

Robin grabbed a chenille bathrobe from the end post of her bed and threw it on over the last of Harry Stillwater’s T-shirts, still wearable as a nightshirt. Tucking her feet into her slippers, she wandered toward the kitchen.

Robin’s bedroom was to the left of a hall dressing room with two mirrored closets. She padded through the hall into the long living room then around the corner into the dining room with its fieldstone fireplace tucked in one corner. Though folding doors could be closed between the living and dining rooms, Robin left them open so flames dancing in the hearth cheered both spaces. An oversized desk with a typing-well faced the dining room, perpendicular to the front door, defining a small front entry. The apartment’s vaulted, uninsulated ceiling leaked when it rained. A Boston fern hanging by a chain from a rafter gathered the drips. The fern’s fronds hung two feet out and down. A large kitchen with oak cabinets and butcher block patterned Formica counters was off the dining room to the right.

Robin made herself coffee in her new drip coffeemaker set on the open counter that separated the kitchen from the dining room. A swag curtain sewn from a sheet hung from the ceiling on the dining room side of the bar further defined the two spaces. As the coffee dripped, Robin congratulated herself for having the fortitude to relegate Harry’s silver percolator to the storage closet at the front of her designated parking space. The image of the percolator thumping while Harry read the Sunday paper still brought her to tears.

Gunner wove between Robin’s legs as she spooned cat food into his bowl. She set the dish on the tray of his highchair. Gunner jumped first onto one of the dining chairs then climbed into his seat. They sat side-by-side at the round dining table Harry had bought for the house that the three never shared.

A soft glow drifted waves of dawn through the windows fronting Robin’s apartment. Robin pulled her bathrobe tight, hungover from too much booze drunk and too much marijuana smoked the previous night. Pot smoking was a one-way ticket out of the Navy. Robin knew better.

No, she didn’t.